Introduction

S. S. Rajamouli’s “Baahubali” series presents Shivudu (later revealed as Mahendra Baahubali) as a mythic hero, shaped by forces larger than personal ambition. While the popular interpretation paints him as a destined king, a Jungian view treats him as a vessel of archetypal energies – the Hero, the Warrior, the Lover, and ultimately, the King. Jung’s analytical psychology views narratives not merely as entertainment, but as symbolic expressions of the psyche, where characters embody universal patterns of human development.

The Hero’s Journey through a Jungian Lens

Joseph Campbell’s monomyth — influenced by Jung’s archetypes — is clearly visible in Shivudu’s arc. His story follows 3 psychological movements:

- Separation: Leaving the familiar (his adoptive tribe and childhood ignorance).

- Initiation: Trials, confrontation with ancestry, confrontation of Shadow (Bhallaladeva’s tyranny).

- Return: Fulfillment of Selfhood, integration of identity, and becoming ruler.

These are not simply plot beats — they are symbolic markers of individuation, the process by which a person moves toward psychological wholeness.

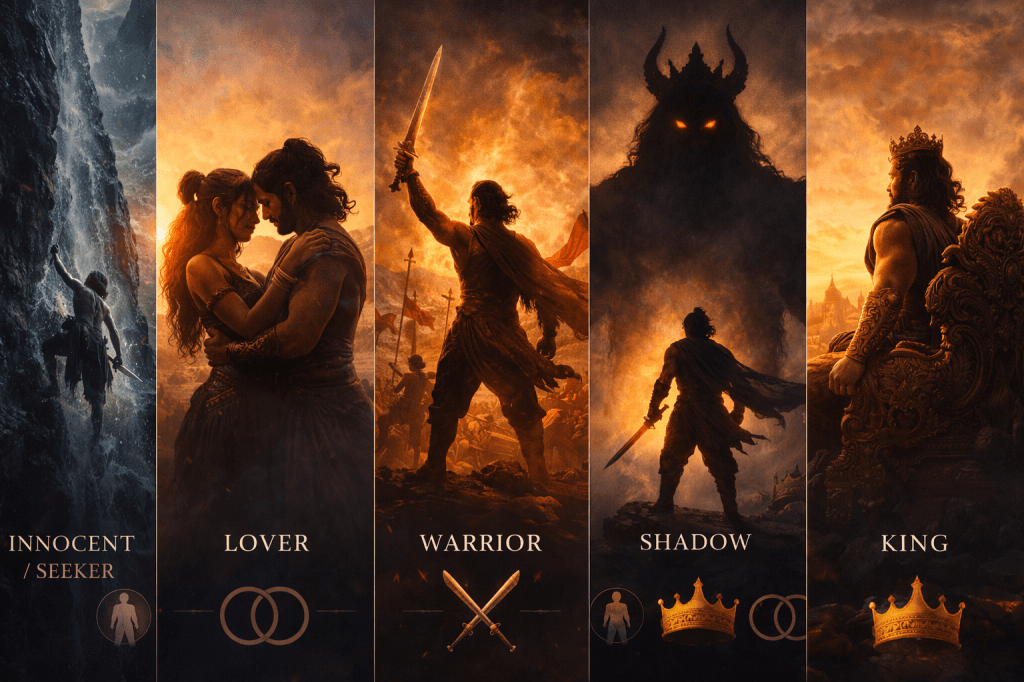

Archetypal Forces in Shivudu

1. The Orphan / Innocent Archetype

Raised away from royal structures, Shivudu grows up instinctively curious. His initial characterization is playful, desirous of ascent — literally climbing waterfalls. The Innocent archetype seeks purity and hope. Psychologists studying mythic narratives in India (e.g., Singh, 2015, Journal of Analytical Psychology – India Edition) note that Indian epics often begin heroes in rural obscurity to symbolize psychological humility. His lack of entitlement is key; individuation always begins in vulnerability, never privilege.

2. The Seeker Archetype

The waterfall symbol is crucial — a motif of aspiration toward the unconscious (water) and transcendence (height). His compulsion to climb is an archetypal “call to adventure.” Jung wrote that unconscious desires manifest as images that “summon the ego toward its task of becoming.” Shivudu’s obsession with the peak represents the human urge for transcendence — a refusal to remain confined to inherited circumstance.

3. The Lover Archetype

His meeting with Avantika awakens eros — but unlike shallow cinematic romance, this phase is psychologically functional. Eros in Jungian theory is the bridge that connects personal will with collective responsibility. Through Avantika, Shivudu discovers his mission — liberation of Devasena — transitioning from personal desire to transpersonal duty. In mythic-psychology studies (Rao, 2018, “Myth, Eros & Duty in Indian Heroic Narratives”), this is termed “eros as social activation,” a pattern especially common in Indian epics where love catalyzes dharma.

4. The Warrior Archetype

Once Shivudu enters Mahishmati, he confronts injustice. The Warrior archetype is not merely violence — it is disciplined aggression in service of moral clarity. Jung wrote that the Warrior must learn “ethical aim,” or else devolve into the Shadow. Shivudu consciously chooses dharma over impulse — a crucial transition that prevents Warrior energy from turning brutal.

5. Shadow Confrontation: Bhallaladeva

Shivudu’s Shadow is not within himself at first — it is externalized through Bhallaladeva. But psychologically, Bhallaladeva represents what Shivudu could become: power without empathy, dominance without individuation. Jung observed that every hero must “integrate, not merely defeat” the Shadow. Symbolically, by restoring justice instead of merely killing the tyrant, Shivudu integrates the rejected moral order of Mahishmati — he restores lawful structure rather than becoming another tyrant.

6. The King Archetype – Completion

Only after:

- Innocence (humility),

- Quest (search),

- Eros (connection),

- Warrior (action),

- Shadow (confrontation)

does Shivudu become capable of the King archetype — which Jung frames as the state of integrated Selfhood.

The King archetype’s role is generative — it must bless, create, empower, and stabilize. His coronation is not just political but psychic — the ego is no longer fragmented. It assumes its rightful place as the conscious mediator between instinct and morality.

Jung’s Individuation and the Indian Context

Jung observed that individuation is culturally influenced. In the Indian philosophical tradition, especially via dharma-centric epics, the ideal hero is one who transcends ego in service of collective moral order. Shivudu’s destiny is not self-expression (a Western theme) but restoration of cosmic justice (an Indian–dharmic theme). Scholars have noted (Chakravarty, 2020, Indian Journal of Myth & Psychology) that Baahubali blends Western hero psychology with dharmic duty — making it psychologically resonant to Indian audiences.

Arc Summary (Archetypal Progression Table)

| Stage (Film) | Archetype Activated | Psychological Function |

|---|---|---|

| Childhood + Waterfall Obsession | Innocent / Seeker | Desire for transcendence; unconscious summons |

| Encounter with Avantika | Lover | Activation of eros leading to purpose |

| Liberation Mission | Warrior | Ethical action in service of dharma |

| Learning his lineage | Orphan + Shadow | Awareness of fragmentation; identity crisis |

| Defeating Bhallaladeva | Warrior facing Shadow | Integration of repressed collective guilt |

| Coronation | King | Individuation fulfilled; Self realized |

Why This Arc Matters Beyond Cinema

Mahendra Baahubali’s story resonates because it mirrors a psychological need that many societies face — especially India: the longing for just leadership. The narrative is not simply fantasy; it is a cultural projection of collective desire for the King archetype during times of political and social instability. Jung argued that heroes emerge in myth when societies unconsciously seek psychological repair.

In that sense, Baahubali is less a person and more a symbolic physician of a cultural psyche.

Conclusion

When examined through Jungian analytical psychology, Shivudu’s arc becomes a case study in the universal journey toward individuation. His path from innocence to kingship is not accidental — it mirrors the archetypal pathway that human beings must undertake internally: confronting instinct, desire, responsibility, shadow, and ultimately aligning ego with moral purpose.

His narrative, though cinematic, is a psychological mirror — illustrating what Jung believed to be the core human task: to become whole.

Leave a comment